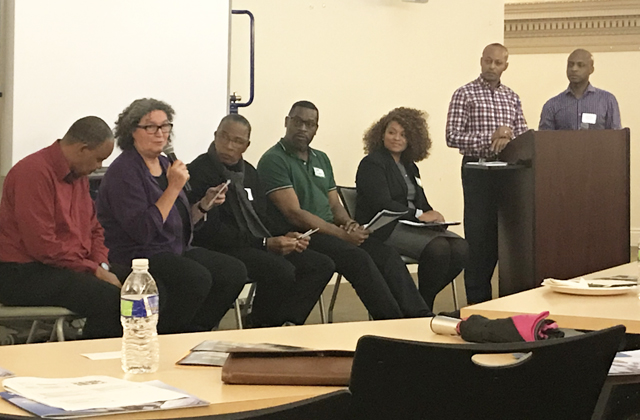

On November 29, the Getting to Zero San Francisco Consortium created space for discussion and reflection on the health inequalities experienced by San Francisco’s Black and African American communities. After an overview of current HIV epidemiology data in San Francisco, presenters discussed the structural challenges that lead to worse health outcomes for African Americans—and the critical need for everyone to address these as part of any city-wide HIV plan.

“We keep seeing health disparities [for African Americans],” said Mike Shriver, co-chair of the HIV Community Planning Council. “We need to re-frame this to be about justice. It’s about economic justice, it’s about gender justice, and it’s about racial justice. Disparity is a way to name the problem, but not own the problem.”

In San Francisco, the highest rates of new HIV infections are among Black men who have sex with men. PrEP—a highly effective method of HIV prevention—is used at a lower rate among people of color. And among people living with HIV, African Americans and Latinos have lower than average rates of viral suppression.

African Americans, although they make up only 5.5% to 6% of the population of San Francisco, account for 12% of people living with HIV and 17% of new infections. More than a quarter—26%—of people who are homeless and living with HIV are African American, shared Shriver.

Why are African Americans disproportionately affected by HIV?

In public health, there has been a history of “polite benign neglect” when it comes to addressing the health disparities faced by African Americans, shared Brett Andrews, CEO of PRC. “But we need to invest.”

“We must bring attention to the fact that institutional and structural racism impact us,” said Vincent Fuqua, from San Francisco Department of Public Health. “A lot of times, people don’t realize that if you’re Black, racism affects you every single day. That leads to stress. And that impacts our health.”

Fuqua shared that it’s impossible to separate the worse health outcomes experienced by African Americans in San Francisco from structural and environmental factors that impact daily life. A history of redlining has pushed Black families out of desirable neighborhoods and has concentrated poverty.

“The median income of African Americans in San Francisco is $20,000 yearly. Imagine what that does to a family,” said Fuqua.

Long-time San Francisco AIDS nurse Diane Jones and San Francisco health commissioner James Loyce both spoke about refusing to “whitewash” the history of HIV.

“We can’t perpetuate the stories that the epidemic was only happening in the four-block radius of the Castro—and wasn’t happening on Polk Street, with young people, in the Mission, in the Tenderloin, in Bayview/Hunters Point, in Oakland, and raging across Africa,” said Jones. “We have to own the disparities that we’ve created, and then only then can we start to fix it.”

Loyce recalled co-founding the Black AIDS Coalition in 1983 and fighting to raise awareness of HIV in the Black community.

“We began to meet because we felt like the AIDS organizations that existed did not acknowledge or recognize how this pandemic was getting to us,” he said. “I joined the board of San Francisco AIDS Foundation in 1986, and my task was to call into question how policies and programs impact the African American community.”

Joe Hawkins shared his thoughts on how the continued gentrification of Bay Area neighborhoods may impact the health of Black community members—and opportunities to better serve Black community members with POC-led spaces.

“I believe we have an opportunity to take advantage of this reality—and serve queer people in a way that leverages the resources of white people to help the most marginalized communities,” he said.

Although we have a variety of ways to turn tide on the HIV epidemic, solutions for the Black community must come with meaningful involvement and leadership from the Black community, explained Loyce.

“You have to shift your thinking in terms of how you work in the African American community,” he said. “This notion that an organization can come in and empower a community is bogus. The community has power. Your job is to go to the community and say, ‘how can I facilitate you exercising your power for your health?’”

—

Getting to Zero is a multi-sector collaboration working to reach zero HIV infections, zero AIDS-related deaths and zero HIV stigma. Find out more about Getting to Zero coalition and how to get involved.

Showing up for Racial Justice (SURJ) is a national network of groups and individuals organizing white people for racial justice. Through community organizing, mobilizing and education, SURJ moves white people to act as part of a multi-racial majority for justice, with passion and accountability. Sign up for a training or event with SURJ.

San Francisco AIDS Foundation provides a variety of services and resource for people of color, by people of color. Find out about community groups including Black Brothers Esteem, DREAAM, Black Health Center of Excellence and Latino Programs and join for an upcoming event. In the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, a group for queer and trans people of color meets Thursdays from 5 pm – 8 pm at Strut (470 Castro Street).